The term “expatriate” is often used to describe people from Western countries, particularly the United States and Europe, who live and work abroad. On the surface, it might seem like just another way to refer to someone living outside their native country. However, a closer examination reveals that the term is fraught with issues and underpinned by a range of socio-political implications. It perpetuates a double standard, reinforcing a hierarchy that differentiates Western migrants from those from other parts of the world. This blog post aims to critique the term “expatriate” and expose how it is used to uphold systemic inequalities and cultural superiority.

Defining the Term

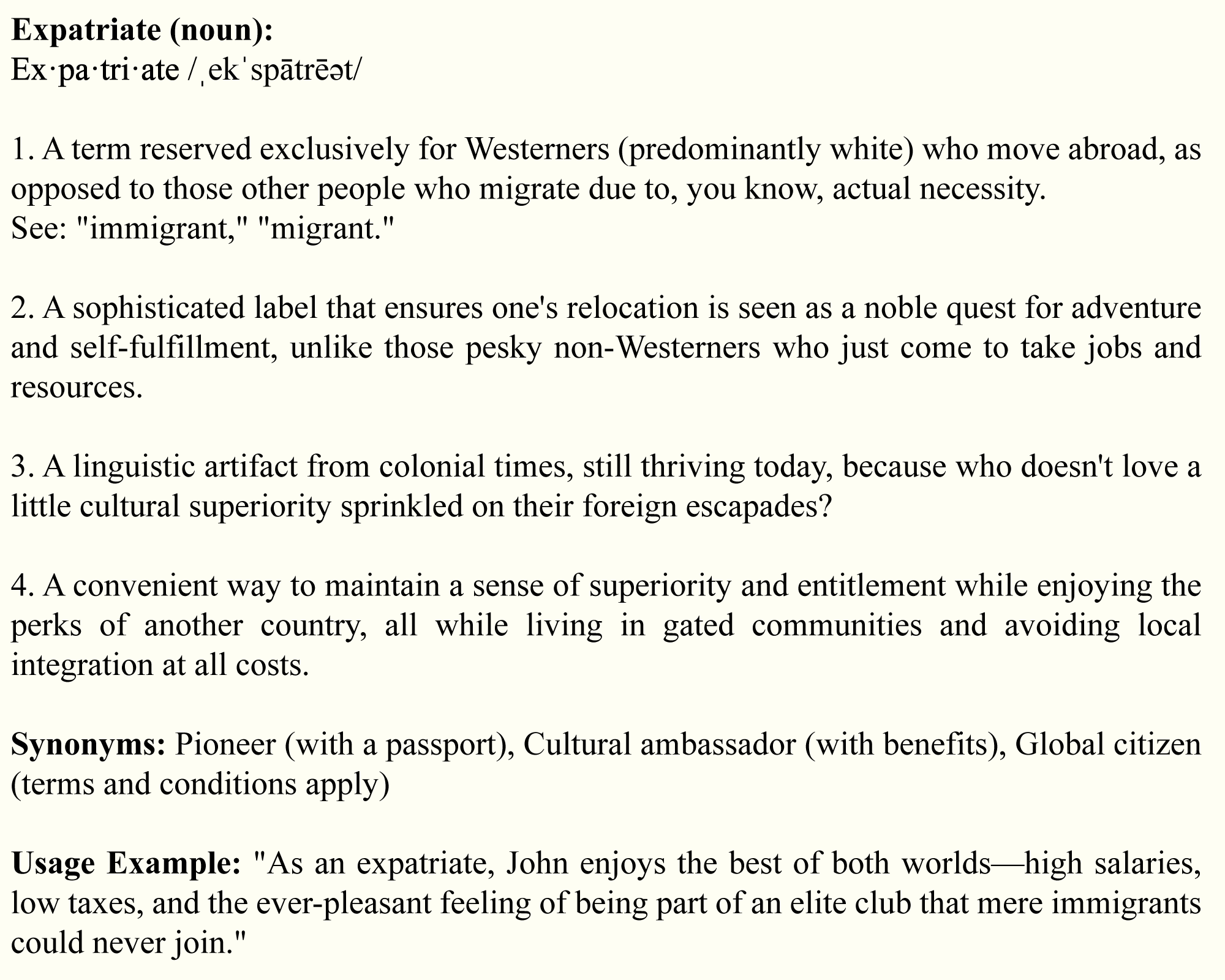

To begin, it’s important to understand what the term “expatriate” generally signifies. Traditionally, it refers to a person who resides outside their native country. However, in practice, it is primarily used to describe Westerners—often white and from affluent backgrounds—who move abroad, typically for work. The term carries with it connotations of privilege, adventure, and choice. In contrast, people from non-Western countries who move abroad are usually labeled as “immigrants” or “migrants,” terms that often evoke images of economic hardship, lack of choice, and a lower social status.

The Implicit Hierarchy

The distinction between “expatriate” and “immigrant” is not just semantic; it reflects and reinforces an implicit hierarchy based on race, nationality, and socioeconomic status. This hierarchy suggests that Western lives are more valuable and that Westerners are entitled to certain privileges, even when living abroad. By using “expatriate” to describe Westerners and “immigrant” to describe everyone else, we perpetuate a narrative that frames Western migration as positive and voluntary, while non-Western migration is seen as problematic and involuntary.

Privilege and Mobility

One of the key issues with the term “expatriate” is that it obscures the privilege that often underlies Western migration. Many Westerners who move abroad do so with significant advantages: they may have access to higher-paying jobs, better legal protections, and the ability to return home whenever they choose. These privileges are not typically extended to immigrants from non-Western countries, who often face restrictive immigration policies, limited job opportunities, and the constant threat of deportation.

Moreover, the term “expatriate” often implies a temporary stay, whereas “immigrant” suggests a more permanent move. This distinction further entrenches the idea that Westerners are merely visitors in other countries, free to come and go as they please, while non-Western migrants are expected to assimilate and often face greater scrutiny and pressure to justify their presence.

Cultural Superiority and Colonial Echoes

The use of “expatriate” also carries echoes of colonialism, where Westerners are seen as bringing civilization, knowledge, and progress to the “less developed” parts of the world. This mindset persists in the way expatriates are often depicted as adventurous pioneers, spreading their culture and expertise. In contrast, immigrants are frequently portrayed as a burden on the host society, taking jobs and resources from the native population.

This cultural superiority is evident in the way expatriate communities often remain segregated from the local population, living in exclusive neighborhoods, sending their children to international schools, and socializing primarily with other expatriates. Such behavior not only perpetuates a sense of separateness but also reinforces the notion that expatriates are above the local population, both culturally and socially.

Language and Power

Language is a powerful tool that shapes our perceptions and interactions. By differentiating between “expatriates” and “immigrants,” we are not just describing different groups of people; we are assigning value and status. The term “expatriate” is a form of soft power, a linguistic tool that allows Westerners to maintain a sense of superiority and control, even when they are the ones moving into other countries.

It’s important to question why we need different terms to describe people who are essentially doing the same thing: moving to a new country to live and work. By critically examining and challenging the use of “expatriate,” we can begin to dismantle the biases and inequalities that this term upholds.

Toward a More Equitable Language

To move toward a more equitable and just society, we must rethink the language we use to describe migration. Instead of perpetuating a hierarchy that privileges Westerners, we should adopt terms that recognize the shared experiences of all migrants, regardless of their country of origin. Terms like “migrant” or “international resident” can help to level the playing field, acknowledging that everyone who moves to a new country faces challenges and deserves respect and dignity.

The term “expatriate” is not just a harmless label; it is a reflection of deep-seated prejudices and power dynamics that favor Westerners over non-Westerners. By critically examining and challenging this term, we can work toward a more inclusive and equitable understanding of migration, one that respects and values the experiences of all people, regardless of their background. Let us strive to create a world where mobility is a right enjoyed by all, not a privilege reserved for a select few.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.